Financial Education

Our advisors share their insights and experience on a wide range of financial topics.

Tips to Reducing the Risk of Identity Theft

Every three seconds someone becomes a victim of identity theft. Florida is number one in the country for identity theft complaints. Naples is number three in the country nationwide for identity theft complaints. No one is immune from identity theft. In fact, there is nothing you can do or a service you can buy that will prevent it from happening to you. However, there are steps you can take to reduce your risk of becoming a victim.

MySSA

The Social Security Administration (SSA) has launched My Social Security Account (MySSA) which permits you to manage your benefits online. To create your account visit www.SSA.gov and click in the box where it says “my Social Security”. You will be required to enter your name, address, date of birth and social security number. Note: the site uses the latest security measures to protect your information. Next you will be asked a series of questions based on your Experian credit report. Questions such as: how much is your mortgage payment, what is the address of the property where you have the mortgage, or how much is your car loan payment. After answering the questions you will be able to view your benefits. You can also change your deposit account or you can file for benefits if you are not yet receiving them. Unfortunately thieves have been using this system to steal your benefits. To prevent this from happening to you have two options:

- Create your MySSA account online, as mentioned above

- Block electronic access to your information online or by calling the SSA at 1-800-772-1213

The act of either setting up your account or requesting to block electronic access will prevent someone else from creating an account using your information. If, when you are attempting to create or block your account, you are notified you already have an account you may already be a victim. You will need to contact Social Security to notify them of the potential fraud and inquire about the procedures to correct the problem.

Credit Reports

Per federal regulation you are entitled to receive one free credit report from each credit bureau (Experian, Equifax and TransUnion) every twelve months. To order and review your credit reports online visit www.annualcreditreport.com. You will be required to enter your sensitive information. You will also be asked a series of questions to verify your identity. Because of this I recommend you do this where you have access to your financial records (mortgage, loan and other information). The process could take an hour or more.

Junk Mail Opt-Out

There are two ways to stop the junk mail you receive such as pre-approved credit card offers, magazine subscriptions, offers for services, etc.

- DMAchoice.org was created by the Direct Marketing Association to block unwanted solicitations. Visit their website, enter your information (name, street address and email address) and then list your opting-out preference(s). You can choose to opt-out of specific categories of direct mail or all categories of direct mail. This service is free of charge. If you prefer to register by mail you can download the registration form from www.DMAchoice.org. The fee to register by mail is $1.00.

- OptOutPrescreen.com allows you to opt-out from receiving pre-approved credit card offers. This program reports directly to the credit bureaus Experian, Equifax, TransUnion and Innovus. You can register online or by calling 888-567-8688. Once registered will receive a confirmation letter. You have the option to sign the confirmation letter and return it to OptOutPrescreen. Doing so will make your registration permanent. If you choose to not return the confirmation page your registration will be valid for five years.

These are just a few of the tips to reduce your risk of becoming a victim of identity theft. If you would like additional information you can visit my website CarrieKerskie.com. There you can read articles and register for my free electronic newsletter. You only need to enter your name and email address. I promise that I will not sell, rent, lease, or share your information. I am here to help. If you have a question or need assistance give me a call or send me an email.

Contact Information:

Carrie Kerskie

(239) 435-9111

Email: ck@kerskie.com

Website: www.Kerskie.com

Blog: www.CarrieKerskie.com

Twitter: @carriekerskie

Carrie Kerskie and the views expressed in this article are not necessarily the opinion of, nor is she, affiliated with Ciccarelli Advisory Services, Inc. or FSC Securities Corporation.

Recovering from Identity Theft

Organize your fight against crime •Be prepared with the information you’ll need to give •Keep a log of your conversations (dates, names of the people you speak with, and a summary of what’s discussed •Follow up in writing •Keep copies of your correspondence •Keep the originals of supporting documents; send copies •Keep old files even after the case is closed, just in case

You’ve read about it, and you thought it would never happen to you. But suddenly your bank account is empty, your credit card bills are through the roof, and you’re getting late notices for accounts you don’t own. Your identity has been stolen. What now?

Time is money

To minimize your losses, act fast. Contact, in this order:

- Your credit card companies

- Your bank

- The three major credit bureaus

- Local, state, or federal law enforcement authorities

Your credit card companies

Credit card companies are getting better at detecting fraud; in many cases, if they spot activity outside the mainstream of your normal card usage, they’ll call you to confirm that you made the charges. But the responsibility to notify them of lost or stolen cards is still yours.

If you do so in a reasonable time (within 30 days after you discover the loss), you won’t be responsible for more than $50 per card in fraudulent charges. Ask that the accounts be closed at your request, and open new accounts with password protection.

If an identity thief opens new accounts in your name, you’ll need to prove it wasn’t you who opened them. Ask the creditors for copies of application forms or other transaction records to verify that the signature on them isn’t yours.

Follow up your initial creditor contacts with letters indicating the date you reported the loss or theft. Watch your subsequent monthly statements from the creditor; if any fraudulent charges appear, contest them in writing.

Your bank

If your debit (ATM) card is lost or stolen, you won’t be held responsible for any unauthorized withdrawals if you report the loss before it’s used. Otherwise, the extent of your liability depends on how quickly you report the loss.

- If you report the loss within two business days after you notice the card is missing, you’ll be held liable for up to $50 of unauthorized withdrawals. (If the card doubles as a credit card, you may not be protected by this limit.)

- If you fail to report the loss within two days after you notice the card is missing, you can be held responsible for up to $500 in unauthorized withdrawals.

- If you fail to report an unauthorized transfer or withdrawal that’s posted on your bank statement within 60 days after the statement is mailed to you, you risk unlimited loss.

If your checkbook is lost or stolen, stop payment on any outstanding checks, then close the account and open a new one. Dispute any fraudulent checks accepted by merchants in order to prevent collection activity against you.

The three major credit bureaus

If your credit cards have been lost or stolen, call the fraud number of any one of the three national credit reporting agencies:Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. You need to contact only one of the three; the one you call is required to contact the other two.

Next, place a fraud alert on your credit report. If your credit cards have been lost or stolen, and you think you may be victimized by identity theft, you may place an initial fraud alert on your report. If you become a victim of identity theft (an existing account is used fraudulently or the thief opens new credit in your name), you may place an extended fraud alert on your credit report once you file a report with a law enforcement agency.

Once a fraud alert has been placed on your credit report, any user of your report is required to verify your identity before extending any existing credit or issuing new credit in your name. For extended fraud alerts, this verification process must include contacting you personally by telephone at a number you provide for that purpose.

Most states now allow you to “freeze” your credit report. (In the few that don’t, the credit bureaus allow state residents to freeze their reports voluntarily.) Once you freeze your report, no one–creditors, insurers, and even potential employers–will be allowed access to your credit report unless you “thaw” it for them.

To freeze your credit report, you must contact all three major credit reporting agencies. In many cases, victims of identity theft are not charged a fee to freeze and/or thaw their credit reports, but the laws vary from state to state. Contact the office of the attorney general in your state for more information.

If you discover fraudulent transactions on your credit reports, contest them through the credit bureaus. Do so in writing, and provide a copy of the identity theft report you file. You should also contest the fraudulent transaction in the same fashion with the merchant, bank, or creditor who reported the information to the credit bureau. Both the credit bureaus and those who provide information to them are responsible for correcting fraudulent information on your credit report, and for taking pains to assure that it doesn’t resurface there.

Law enforcement agencies

While the police may not catch the person who stole your identity, you should file a report about the theft with a federal, state, or local law enforcement agency. Once you’ve filed the report, get a copy of it; you’ll need it in order to file an extended fraud alert with the credit bureaus. You may also need to provide it to banks or creditors before they’ll forgive any unauthorized transactions.

When you file the report, give the law enforcement officer as much information about the crime as possible: the date and location of the loss or theft, information about any existing accounts that have been compromised, and/or information about any new credit accounts that have been opened fraudulently. Write down the name and contact information of the investigator who took your report, and give it to creditors, banks, or credit bureaus that may need to verify your case.

If the theft of your identity involved any mail tampering (such as stealing credit card offers or statements from your mailbox, or filing a fraudulent change of address form), notify the U.S. Postal Inspection Service. If your driver’s license has been used to pass bad checks or perpetrate other forms of fraud, contact your state’s Department of Motor Vehicles. If you lose your passport, contact the U.S. Department of State. Finally, if your Social Security card is lost or stolen, notify the Social Security Administration.

Follow through

Once resolved, most instances of identity theft stay resolved. But stay alert: Monitor your credit reports regularly, check your monthly statements for any unauthorized activity, and be on the lookout for other signs (such as missing mail and debt collection activity) that someone is pretending to be you.

Prepared by Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. Copyright 2015.

Net Unrealized Appreciation: The Untold Story

If you participate in a 401(k), ESOP, or other qualified retirement plan that lets you invest in your employer’s stock, you need to know about net unrealized appreciation–a simple tax deferral opportunity with an unfortunately complicated name.

When you receive a distribution from your employer’s retirement plan, the distribution is generally taxable to you at ordinary income tax rates. A common way of avoiding immediate taxation is to make a tax-free rollover to a traditional IRA. However, when you ultimately receive distributions from the IRA, they’ll also be taxed at ordinary income tax rates. (Special rules apply to Roth and other after-tax contributions that are generally tax free when distributed.)

But if your distribution includes employer stock (or other employer securities), you may have another option–you may be able to defer paying tax on the portion of your distribution that represents net unrealized appreciation (NUA). You won’t be taxed on the NUA until you sell the stock. What’s more, the NUA will be taxed at long-term capital gains rates–typically much lower than ordinary income tax rates. This strategy can often result in significant tax savings.

What is net unrealized appreciation?

A distribution of employer stock consists of two parts: (1) the cost basis (that is, the value of the stock when it was contributed to, or purchased by, your plan), and (2) any increase in value over the cost basis until the date the stock is distributed to you. This increase in value over basis, fixed at the time the stock is distributed in-kind to you, is the NUA.

For example, assume you retire and receive a distribution of employer stock worth $500,000 from your 401(k) plan, and that the cost basis in the stock is $50,000. The $450,000 gain is NUA.

How does it work?

At the time you receive a lump-sum distribution that includes employer stock, you’ll pay ordinary income tax only on the cost basis in the employer securities. You won’t pay any tax on the NUA until you sell the securities. At that time the NUA is taxed at long-term capital gain rates, no matter how long you’ve held the securities outside of the plan (even if only for a single day). Any appreciation at the time of sale in excess of your NUA is taxed as either short-term or long-term capital gain, depending on how long you’ve held the stock outside the plan.

Using the example above, you would pay ordinary income tax on $50,000, the cost basis, when you receive your distribution. (You may also be subject to a 10% early distribution penalty if you’re not age 55 or totally disabled.) Let’s say you sell the stock after ten years, when it’s worth $750,000. At that time, you’ll pay long-term capital gains tax on your NUA ($450,000). You’ll also pay long-term capital gains tax on the additional appreciation ($250,000), since you held the stock for more than one year. Note that since you’ve already paid tax on the $50,000 cost basis, you won’t pay tax on that amount again when you sell the stock.

If your distribution includes cash in addition to the stock, you can either roll the cash over to an IRA or take it as a taxable distribution. And you don’t have to use the NUA strategy for all of your employer stock–you can roll a portion over to an IRA and apply NUA tax treatment to the rest.

What is a lump-sum distribution?

In general, you’re allowed to use these favorable NUA tax rules only if you receive the employer securities as part of a lump-sum distribution. To qualify as a lump-sum distribution, both of the following conditions must be satisfied:

- It must be a distribution of your entire balance, within a single tax year, from all of your employer’s qualified plans of the same type (that is, all pension plans, all profit-sharing plans, or all stock bonus plans)

- The distribution must be paid after you reach age 59½, or as a result of your separation from service, or after your death

There is one exception: even if your distribution doesn’t qualify as a lump-sum distribution, any securities distributed from the plan that were purchased with your after-tax (non-Roth) contributions will be eligible for NUA tax treatment.

NUA is for beneficiaries, too

If you die while you still hold employer securities in your retirement plan, your plan beneficiary can also use the NUA tax strategy if he or she receives a lump-sum distribution from the plan. The taxation is generally the same as if you had received the distribution. (The stock doesn’t receive a step-up in basis, even though your beneficiary receives it as a result of your death.)

If you’ve already received a distribution of employer stock, elected NUA tax treatment, and die before you sell the stock, your heir will have to pay long-term capital gains tax on the NUA when he or she sells the stock. However, any appreciation as of the date of your death in excess of NUA will forever escape taxation because, in this case, the stock will receive a step-up in basis. Using our example, if you die when your employer stock is worth $750,000, your heir will receive a step-up in basis for the $250,000 appreciation in excess of NUA at the time of your death. If your heir later sells the stock for $900,000, he or she will pay long-term capital gains tax on the $450,000 of NUA, as well as capital gains tax on any appreciation since your death ($150,000). The $250,000 of appreciation in excess of NUA as of your date of death will be tax free.

Some additional considerations

- If you want to take advantage of NUA treatment, make sure you don’t roll the stock over to an IRA. That will be irrevocable, and you’ll forever lose the NUA tax opportunity.

- You can elect not to use the NUA option. In this case, the NUA will be subject to ordinary income tax (and a potential 10% early distribution penalty) at the time you receive the distribution.

- Stock held in an IRA or employer plan is entitled to significant protection from your creditors. You’ll lose that protection if you hold the stock in a taxable brokerage account.

- Holding a significant amount of employer stock may not be appropriate for everyone. In some cases, it may make sense to diversify your investments.

- Be sure to consider the impact of any applicable state tax laws.

When is it the best choice?

In general, the NUA strategy makes the most sense for individuals who have a large amount of NUA and a relatively small cost basis. However, whether it’s right for you depends on many variables, including your age, your estate planning goals, and anticipated tax rates. In some cases, rolling your distribution over to an IRA may be the better choice. And if you were born before 1936, other special tax rules might apply, making a taxable distribution your best option.

Prepared by Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. Copyright 2015.

How Much Annual Income Can Your Retirement Portfolio Provide?

Your retirement lifestyle will depend not only on your assets and investment choices, but also on how quickly you draw down your retirement portfolio. The annual percentage that you take out of your portfolio, whether from returns or the principal itself, is known as your withdrawal rate. Figuring out an appropriate initial withdrawal rate is a key issue in retirement planning and presents many challenges.

Why is your withdrawal rate important?

Take out too much too soon, and you might run out of money in your later years. Take out too little, and you might not enjoy your retirement years as much as you could. Your withdrawal rate is especially important in the early years of your retirement; how your portfolio is structured then and how much you take out can have a significant impact on how long your savings will last.

Gains in life expectancy have been dramatic. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, people today can expect to live more than 30 years longer than they did a century ago. Individuals who reached age 65 in 1950 could anticipate living an average of 14 years more, to age 79; now a 65-year-old might expect to live for roughly an additional 19 years. Assuming rising inflation, your projected annual income in retirement will need to factor in those cost-of-living increases. That means you’ll need to think carefully about how to structure your portfolio to provide an appropriate withdrawal rate, especially in the early years of retirement.

Current Life Expectancy Estimates

Men: at birth – 76.4, at age 65 – 82.9

Women: at birth – 81.2, at age 65 – 85.5

Source: NCHS Data Brief, Number 168, October 2014

Conventional wisdom

So what withdrawal rate should you expect from your retirement savings? The answer: it all depends. The seminal study on withdrawal rates for tax-deferred retirement accounts (William P. Bengen, “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data,” Journal of Financial Planning, October 1994) looked at the annual performance of hypothetical portfolios that are continually rebalanced to achieve a 50-50 mix of large-cap (S&P 500 Index) common stocks and intermediate-term Treasury notes. The study took into account the potential impact of major financial events such as the early Depression years, the stock decline of 1937-1941, and the 1973-1974 recession. It found that a withdrawal rate of slightly more than 4% would have provided inflation-adjusted income for at least 30 years.Conventional wisdom

Other later studies have shown that broader portfolio diversification, rebalancing strategies, variable inflation rate assumptions, and being willing to accept greater uncertainty about your annual income and how long your retirement nest egg will be able to provide an income also can have a significant impact on initial withdrawal rates. For example, if you’re unwilling to accept a 25% chance that your chosen strategy will be successful, your sustainable initial withdrawal rate may need to be lower than you’d prefer to increase your odds of getting the results you desire. Conversely, a higher withdrawal rate might mean greater uncertainty about whether you risk running out of money. However, don’t forget that studies of withdrawal rates are based on historical data about the performance of various types of investments in the past. Given market performance in recent years, many experts are suggesting being more conservative in estimating future returns.

Note: Past results don’t guarantee future performance. All investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal, and there can be no guarantee that any investing strategy will be successful.

Inflation is a major consideration

To better understand why suggested initial withdrawal rates aren’t higher, it’s essential to think about how inflation can affect your retirement income. Here’s a hypothetical illustration; to keep it simple, it does not account for the impact of any taxes. If a $1 million portfolio is invested in an account that yields 5%, it provides $50,000 of annual income. But if annual inflation pushes prices up by 3%, more income–$51,500–would be needed next year to preserve purchasing power. Since the account provides only $50,000 income, an additional $1,500 must be withdrawn from the principal to meet expenses. That principal reduction, in turn, reduces the portfolio’s ability to produce income the following year. In a straight linear model, principal reductions accelerate, ultimately resulting in a zero portfolio balance after 25 to 27 years, depending on the timing of the withdrawals.

Volatility and portfolio longevity

When setting an initial withdrawal rate, it’s important to take a portfolio’s ups and downs into account–and the need for a relatively predictable income stream in retirement isn’t the only reason. According to several studies done in the late 1990s and updated in 2011 by Philip L. Cooley, Carl M. Hubbard, and Daniel T. Walz, the more dramatic a portfolio’s fluctuations, the greater the odds that the portfolio might not last as long as needed. If it becomes necessary during market downturns to sell some securities in order to continue to meet a fixed withdrawal rate, selling at an inopportune time could affect a portfolio’s ability to generate future income.

Making your portfolio either more aggressive or more conservative will affect its lifespan. A more aggressive portfolio may produce higher returns but might also be subject to a higher degree of loss. A more conservative portfolio might produce steadier returns at a lower rate, but could lose purchasing power to inflation.

Calculating an appropriate withdrawal rate

Your withdrawal rate needs to take into account many factors, including (but not limited to) your asset allocation, projected inflation rate, expected rate of return, annual income targets, investment horizon, and comfort with uncertainty. The higher your withdrawal rate, the more you’ll have to consider whether it is sustainable over the long term.

Ultimately, however, there is no standard rule of thumb; every individual has unique retirement goals, means, and circumstances that come into play.

Prepared by Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. Copyright 2015.

Good News for 529 Plan Savers: More Investment Flexibility

Call it a holiday gift. Thanks to legislation passed in December, beginning in 2015, owners of 529 accounts will be able to change the investment options on their existing plan contributions twice per calendar year instead of just once. This increased flexibility is a welcome option for parents and grandparents who use 529 plans to save for their children’s or grandchildren’s college education.

Call it a holiday gift. Thanks to legislation passed in December, beginning in 2015, owners of 529 accounts will be able to change the investment options on their existing plan contributions twice per calendar year instead of just once. This increased flexibility is a welcome option for parents and grandparents who use 529 plans to save for their children’s or grandchildren’s college education.

Previously, if an account owner had exhausted his or her once-per-year investment change allowance, the only way to change investment options again on existing contributions in the same year was to change the beneficiary of the account, which may not have been desirable or feasible.

Many college savers–and even states that manage 529 plans–have characterized the once-per-year rule as too restrictive and have called for changing it. Congress listened once before. During the stock market downturn that began in 2008, Congress passed a rule allowing 529 account owners to change their investment options on existing contributions twice per year, but only for 2009. The once-per-year rule kicked back in for 2010.

Although a jump from one investment change to two isn’t earth-shattering (some would argue it’s not nearly enough), it still offers a bit more flexibility for 529 plan savers who want to make an additional investment change during the same calendar year.

Note: Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses associated with 529 plans before investing. More information about specific 529 plans is available in each issuer’s official statement, which should be read carefully before investing. Also, before investing, consider whether your state offers a 529 plan that provides residents with favorable state tax benefits. As with other investments, there are generally fees and expenses associated with participation in a 529 savings plan. There is also the risk that the investments may lose money or not perform well enough to cover college costs as anticipated.

Prepared by Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. Copyright 2014

Video – Data Breaches: Fighting Identity Theft with New Technologies

Deductions: Charitable Gifts

What is a charitable gift?

A charitable gift is a contribution of cash or property to, or for the use of, a qualified charity. A gift is “for the use of” an organization when it’s held in a legally enforceable trust for the qualified organization or in a similar legal arrangement. Americans give billions of dollars to charities each year, partly because charitable donations are tax deductible. To receive a tax deduction for your gift, you must itemize your deductions and make the gift to a qualified organization, not to a specific person. For example, a gift that’s for the benefit of an individual flood victim isn’t deductible, but a gift to a qualified organization that helps flood victims generally is deductible.

Tip: For tax years prior to 2014, persons aged 70½ and older can exclude from their gross income qualified charitable distributions of up to $100,000 a year from a traditional IRA or a Roth IRA. Distributions must be made directly from the IRA to the charity, and all the usual requirements for charitable deductions must be met.

Tip: To deduct a charitable contribution, you must file Form 1040 and itemize deductions on Schedule A.

What is a qualified organization?

In general:

Not all contributions to tax-exempt organizations are tax-deductible. Instead, the contribution must be to a qualified organization. Churches, synagogues, temples, mosques, and governments automatically get qualified organization status. Other organizations must apply to the IRS, which provides data on eligible organizations on its website (www.irs.gov) through its Exempt Organizations Select Check tool. The list maintained by the IRS, however, is not all-inclusive (i.e., there are some qualified organizations for which the deductions are tax deductible that aren’t yet on the list). If you want to donate to a charity but you’re not sure if it’s a qualified organization, ask the charity or the IRS.

Five specific types of qualified organizations:

- Any community chest, corporation, trust, fund, or foundation organized or created in or under the laws of the United States, any state, the District of Columbia, or any U.S. possession and operated solely for religious, charitable, educational, scientific, or literary purposes or for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals. For example, organizations such as the Red Cross, the United Way, and the Salvation Army fall within this category, as does the National Park Foundation.

- War veterans’ organizations, including posts, auxiliaries, trusts, or foundations organized in the United States or its possessions.

- Domestic fraternal societies, orders, and associations operating under the lodge system–if your contribution is to be used solely for charitable, religious, scientific, literary, or educational purposes or for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals.

- Certain nonprofit cemetery companies or corporations–if your contribution is not to be used for the care of a specific lot or mausoleum crypt.

- The United States or any state, the District of Columbia, a U.S. possession, a political subdivision of a state or U.S. possession, or an Indian tribal government or any of its subdivisions that performs a substantial government function–if the contribution is to be used solely for public purposes.

Charitable contributions in general

Generally, you can deduct a contribution of money or property that you make to, or for the use of, a qualified organization. The amount that you can deduct in any given year is limited to a specific percentage of your adjusted gross income (AGI), as discussed in the following sections. If you receive a benefit as a result of making a contribution, you can deduct only the amount of your contribution that exceeds the value of the benefit received.

You may deduct your entire payment to a charity if you receive only a token item in return and the charity correctly tells you (1) that the item’s value isn’t substantial, and (2) that you can deduct your full payment.

If you make a contribution to a college or university and as a result receive the right to buy tickets to an athletic event in the facility’s athletic stadium, you can deduct 80 percent of your payment as a charitable contribution.

Limits based on adjusted gross income (AGI)

Deductions limited to 50 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI)

Your deduction for charitable contributions cannot amount to more than 50 percent of your AGI for the year, and lower percentage limits can apply, depending on the type of property that you give and the type of organization to which you contribute. The 50 percent limit applies to gifts you make to qualified organizations that are public charities or private operating foundations, such as churches, certain educational organizations, hospitals, and certain medical research organizations associated with the hospitals. Most organizations can tell you whether or not they are 50 percent limit organizations.

Deductions limited to 30 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI)

- Your deduction for charitable contributions made to organizations that are not 50 percent limit organizations (see above) cannot be more than 30 percent of your AGI for the year. Organizations that are not considered 50 percent limit organizations include veterans’ organizations, fraternal societies, nonprofit cemeteries, and certain private nonoperating foundations.

- In addition, if you make a charitable contribution for the use of any organization (e.g., you make a gift in trust), as compared with an outright gift, your deduction is limited to 30 percent of your AGI.

- Capital gain property (property that would have resulted in realized long-term capital gains if sold) given to a 50 percent limit organization is also subject to the 30 percent limit.

Caution: The 30 percent limit does not apply when you choose to reduce the fair market value (FMV) of the property by the amount that represents the long-term gain that would result if you sold the property. In this case, the 50 percent limit applies.

Deductions limited to 20 percent of adjusted gross income

All gifts of capital gain property, to or for the use of organizations that are not 50 percent limit organizations, are limited to 20 percent of your AGI.

Five-year carryover of unused charitable deductions

You can carry over your contributions that you aren’t able to deduct in the current year because they exceed your AGI limits. You can deduct this carryover amount until it is used up but not beyond five years. The same AGI percentage limitations that apply in the year the deduction originated will apply in the year(s) to which it is carried. So, for example, contributions subject to a 20 percent AGI limitation this year will be subject to a 20 percent AGI limitation if carried forward to a future year.

Caution: Special rules apply if you use the standard deduction (rather than itemizing) in any of the years in which you carry forward unused charitable deductions. Essentially, the carryover amount must be reduced by the amount that you would have been able to deduct had you itemized.

Example(s): Jack’s AGI for the current tax year is $50,000. In August of the current tax year, he gave his church $2,000 in cash (a 50 percent charity). He also gave his church land with an FMV of $30,000 and a basis of $22,000. The land was held for investment for more than 12 months. The donation of the land is subject to the special 30 percent limitation. He also gave $5,000 of capital gain property to a private foundation that is a non-50 percent charity. The $5,000 contribution is subject to the 20 percent limitation.

Example(s): Jack’s charitable contribution deduction is computed as follows: The total charitable contribution deduction can’t exceed $25,000 (50 percent of $50,000). The cash contribution is considered first, since Jack made it to a 50 percent charity. Other charitable contributions are considered in the following order, not to exceed 50 percent of AGI in the aggregate:

- Contributions of noncapital gain property to non-50 percent charities, to the extent of the lesser of: (a) 30 percent of AGI, or (b) 50 percent of AGI reduced by all contributions to 50 percent charities.

- Contributions of capital gain property to 50 percent charities, up to 30 percent of AGI.

- Contributions of capital gain property to non-50 percent charities, to the extent of the lesser of: (a) 20 percent of AGI, or (b) 30 percent of AGI less contributions of capital gain property to 50 percent charities.

Example(s): Jack’s donation of land to the church is subject to the special 30 percent of AGI limit described in item 2. It is included at FMV ($30,000) in applying the 30 percent limitation. Therefore, Jack can deduct a maximum of $15,000 (30 percent of $50,000 AGI) for the donation of the land. The unused special 30 percent contribution ($15,000) may be carried over to later years. The $5,000 contribution to the private foundation is nondeductible because of the limitation described in item 3 [(30 percent of $50,000 AGI) – $30,000 contribution of land = 0] and carries over to the following tax year.

Example(s): Therefore, Jack’s current tax year deduction is limited to $17,000 ($2,000 + $15,000). The aggregate 50 percent limitation wasn’t reached. Both carryovers continue to be subject to the special 30 percent and 20 percent limits, respectively.

What if you give property instead of cash?

You generally can deduct the fair market value (FMV) of the property at the time you give it to the charity. FMV is the price a willing seller receives from a willing buyer for the property, with both knowing relevant facts about the property. If the property has gone up in value since you purchased it, you may have to make an adjustment to the amount of your deduction (generally this is true if, had you sold the property, you would have recognized ordinary income or short-term capital gain–in such a case, the amount you can deduct may be limited to FMV less the amount that would have been ordinary income or short-term capital gain if you had sold the property). If the property has decreased in value, you may deduct its FMV. IRS Publication 561 (Determining the Value of Donated Property) can help you to determine FMV.

Caution: An accurate assessment is important because you may be liable for a special penalty if you overstate the value of donated property and underpay your tax by more than $5,000 due to the overstatement.

In general, you cannot deduct a charitable contribution of less than your entire interest in property. That normally includes a contribution of the right to use your property (since that represents less than your entire interest in the property). There are exceptions to the partial interest rule, however, including the donation of a remainder interest in your home.

If you contribute property that’s subject to a debt or mortgage, for purposes of calculating your deduction you generally have to reduce the FMV of the property by any allowable deduction for interest you have paid (or will pay) that is attributable to any period after the contribution. (This prevents you from taking the same amount as both an interest deduction and a charitable deduction.)

Special rules apply to the contribution of certain types of property, including clothing and household items, as well as cars, boats, and airplanes. For example, you cannot take a deduction for clothing or household items donated unless the clothing or household items are in good used condition or better. However, an exception exists if you claim more than $500 for an individual item and include a qualified appraisal with your return.

If you donate a patent or other intellectual property, your deduction is limited to the basis of the property or the FMV of the property, whichever is less. You also may be able to claim additional charitable contribution deductions in the year of the contribution and years following, based on any income generated by the donated property. Your ability to claim additional deductions based on the earnings of the donated intellectual property is subject to limitation, and is phased out over a 12-year period. Consult a tax professional.

Can you deduct your out-of-pocket expenses?

If you incur expenses while providing services to a qualified organization, you may generally deduct unreimbursed amounts that are directly connected with the services you provided. For example, you may deduct the cost and upkeep of uniforms that you must wear while performing charitable services if the uniforms aren’t appropriate for everyday use. You can also deduct car expenses, such as gas and oil, if they’re directly related to using your car to provide services and you can provide reliable written records of your expenses. Instead of deducting actual expenses, you can choose to deduct a standard mileage rate of 14 cents per mile. You can also deduct parking and tolls. Depreciation and insurance are not deductible.

If you travel away from home to perform services as a chosen representative for the qualified charity, you can deduct the expenses you incur if there’s no significant element of personal pleasure, recreation, or vacation in the travel. This doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy yourself while providing charitable services. It does mean, however, that you can’t deduct the expenses of a Caribbean cruise just because you provide nominal charitable services while on the boat. If you receive a daily allowance from the charity to cover your reasonable travel expenses, you must include in your income the amount of that allowance that is more than your deductible travel expenses. You may still be able to deduct the amount you spend over the allowance. Deductible travel expenses include air, rail, or bus transportation; out-of-pocket expenses for your car; transportation between the airport or station and your hotel; lodging costs; and the cost of meals.

What kinds of contributions aren’t deductible?

In general, the following cannot be deducted as charitable contributions:

- A contribution to a specific person –You may deduct a donation to a qualified organization that provides aid to the homeless but not a donation to a homeless person you encounter on the street.

- A contribution to a non-qualified organization –The organization must meet IRS criteria of a qualified organization.

- Any part of your contribution from which you receive or expect to receive a benefit –You can deduct only the amount of your donation that exceeds the value of the benefit you receive. If you pay more than FMV to a charity for merchandise, goods, or services, you may deduct the amount you pay that’s more than the value of the item if you pay it with the intent to make a charitable contribution. (You may deduct your entire payment to a charity if you receive only a token item and the charity correctly tells you (1) that the item’s value isn’t substantial, and (2) that you can deduct your full payment.)

- The value of your time or services –You may deduct unreimbursed amounts that are directly connected with the services you provide and which you incurred only because of the services you gave, but you may not deduct the value of your time or services.

- Your personal expenses –You may not deduct expenses that are your personal, living, or family expenses.

- Certain contributions of partial interests in property –Generally, you may not deduct a transfer of a partial interest in property to a qualified organization. There are some exceptions to the general rule, however, including a contribution of a remainder interest in your personal home or farm; an undivided part of your entire interest; a partial interest that would be deductible if transferred to certain types of trusts; and a qualified conservation contribution.

Qualified conservation contributions

In general, the charitable contribution of a partial interest in property is not deductible. A qualified conservation contribution is an exception to this rule. A qualified conservation contribution is a contribution of a qualified real property interest to a qualified organization exclusively for conservation purposes.

Technical Note: A qualified real property interest is (1) the entire interest of the donor other than a qualified mineral interest, (2) a remainder interest, or (3) a restriction (granted in perpetuity) on the use that may be made of the real property.

Technical Note: Qualified organizations include certain governmental units, public charities that meet certain public support tests, and certain supporting organizations.

Technical Note: Conservation purposes include (1) the preservation of land areas for outdoor recreation by, or for the education of, the general public; (2) the protection of a relatively natural habitat of fish, wildlife, or plants, or similar ecosystem; (3) the preservation of open space (including farmland and forest land) where such preservation will yield a significant public benefit and is either for the scenic enjoyment of the general public or pursuant to a clearly delineated Federal, State, or local governmental conservation policy; and (4) the preservation of an historically important land area or a certified historic structure.

Qualified conservation contributions of capital gain property are generally subject to the same limitations and carryover rules as other charitable contributions of capital gain property (i.e., a related deduction would generally be subject to a 30-percent AGI limitation). However, special rules apply to qualified conservation contributions made prior to tax year 2014.

Under the special rules, the 30-percent AGI limitation that applies to contributions of capital gain property does not apply to qualified conservation contributions. Instead, individuals may deduct the fair market value of any qualified conservation contribution, up to 50 percent (100 percent for qualified farmers and ranchers) of AGI reduced by the total deduction for all other allowable charitable contributions. Qualified conservation contributions are not taken into account in determining the amount of other allowable charitable contributions. Individuals are allowed to carry over any qualified conservation contributions that exceed the AGI limitation for up to 15 years.

Can you deduct the costs of having a foreign exchange student live with you?

Yes. If you meet the criteria, you can deduct qualifying expenses for a foreign or American exchange student. The student must:

- Live in your home under a written agreement between you and a charity as part of a program to provide educational opportunities for the student

- Not be your dependent or relative

- Be a full-time student in the 12th grade or lower at a U.S. school

You can deduct up to $50 per month for each month the student lives with you at least 15 days. Qualifying expenses include books, tuition, food, clothing, transportation, medical and dental care, entertainment, and other amounts you actually spent for the well-being of the student. You may not deduct expenses such as home depreciation, lodging, and general household expenses. You also may not deduct expenses if the student is living with you under a mutual exchange program whereby your child will live with a family in a foreign country.

Record keeping

Cash contributions

For your cash contributions, regardless of the amount, you must keep either a bank record (e.g., cancelled check, credit card statement) or a written communication (receipt or letter) from the charitable organization that shows (1) the name of the charitable organization, (2) the date of the contribution, and (3) the amount of the contribution. If you make a charitable contribution through payroll deduction, you must keep a pay stub, W-2, or other documentation from your employer showing the date and amount of contribution, and a pledge card or other documentation from the qualified organization.

If you claim a deduction for a contribution of $250 or more, you must have an acknowledgment of your contribution from the qualified organization (or certain payroll deduction records). The acknowledgment:

- Must be written

- Must include the amount of cash you contributed; whether the organization provided goods or services as a result of your contribution (and an estimate of the value of such goods or services); and a statement that the only benefit you received was an intangible religious benefit, if that was the case

- Must be in your possession on or before the earlier of the date you file your return for the year you make the contribution, or the due date, including extensions, for filing the return

If the acknowledgment does not show the date of the contribution, you will also need a bank record or receipt that shows when the contribution was made.

A noncash contribution under $250

To deduct a noncash contribution under $250, you must get a receipt from the organization that includes your name, the date, the location of the organization, and a reasonably detailed description of the property. You must also have reliable written records for each item you donated. You are not required to get a written receipt when it is impractical to get one (e.g., at an unattended drop-off site).

A noncash contribution between $250 and $500

You need a receipt like the one required for a noncash contribution under $250, but it must also include details on whether the charity gave you any substantial goods or services for your contribution, as well as a description and good faith estimate of the value of any goods or services you received. You have to get this receipt on or before the earlier of the date you file your return or the due date (including extensions) for filing the return.

A noncash contribution between $500 and $5,000

You need a receipt that includes details on whether the charity gave you any substantial goods or services for your contribution and a description and good faith estimate of the value of any goods or services you received. Additionally, your records must include how and when you got the property and how much you paid for it. You must also complete Form 8283, Noncash Charitable Contributions, and attach it to your return.

A noncash contribution over $5,000

You need a receipt and records like those required for noncash contributions between $500 and $5,000, but you also need a qualified written appraisal of the property from a qualified appraiser. Appraisal fees incurred in determining FMV of donated property are not part of a charitable contribution but can be deducted as a miscellaneous deduction on Schedule A.

Technical Note: The IRS defines a qualified appraiser as an individual who (1) has earned an appraisal designation from a recognized professional appraisal organization or has otherwise met minimum education and experience requirements, (2) regularly performs appraisals for which he or she receives compensation, (3) can demonstrate verifiable education and experience in valuing the type of property for which the appraisal is being made, (4) has not been prohibited from practicing before the IRS at any time during the three years preceding the appraisal, and (5) is not excluded from being a qualified appraiser under Treasury regulations.

A noncash contribution over $500,000

If you claim a deduction of more than $500,000 for a contribution of property, you must attach a qualified appraisal of the property to your return. If you do not attach the appraisal, you cannot deduct your contribution. This does not apply to contributions of cash, inventory, publicly traded stock, or intellectual property.

The information presented here is not specific to any individual’s personal circumstances. To the extent that this material concerns tax matters, it is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, by a taxpayer for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed by law. Each taxpayer should seek independent advice from a tax professional based on his or her individual circumstances. Prepared by Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. Copyright 2014

Key Numbers 2015: Tax reference numbers at a glance

For a printer friendly version, CLICK HERE

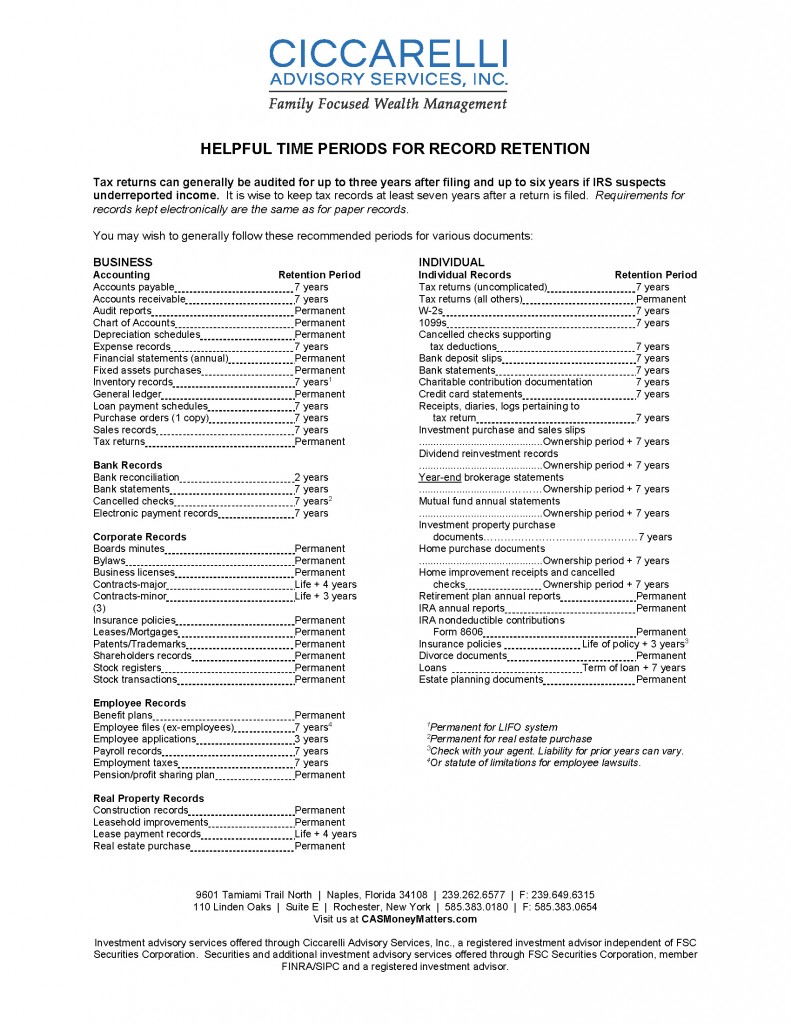

Helpful Time Periods for Record Retention

Tax returns can generally be audited for up to three years after filing and up to six years if the IRS suspects under-reported income. It is wise to keep tax records at least seven years after a return is filed. Requirements for records kept electronically are the same as for paper records.

You may wish to generally follow these recommended periods for various documents…

For a printer friendly version, CLICK HERE

The New Estate Tax Rules and Your Estate Plan

Looking ahead

For 2013 and later years, the 2012 Tax Act permanently extended the $5 million (as indexed for inflation) gift and estate tax exemption and GST tax exemption, and portability of the gift and estate tax exemption, but it also increased the top gift, estate, and GST tax rate to 40%.

Gifts

The large exemptions may make it easier than ever to make large gifts, but they may also reduce the need to make large gifts in order to reduce the gross estate for estate tax purposes.

The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (the 2010 Tax Act) included new gift, estate, and generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax provisions. The 2010 Tax Act provided that in 2011 and 2012, the gift and estate tax exemption was $5 million (indexed for inflation in 2012), the GST tax exemption was also $5 million (indexed for inflation in 2012), and the maximum rate for both taxes was 35%. New to estate tax law was gift and estate tax exemption portability: generally, any gift and estate tax exemption left unused by a deceased spouse could be transferred to the surviving spouse in 2011 and 2012. The GST tax exemption, however, is not portable. Starting in 2013, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (the 2012 Tax Act) permanently extended the $5 million (as indexed for inflation, and thus $5,430,000 in 2015, $5,340,000 in 2014) exemptions and portability of the gift and estate tax exemption, but also increased the top gift, estate, and GST tax rate to 40%. You should understand how these new rules may affect your estate plan.

Exemption portability

Under prior law, the gift and estate tax exemption was effectively “use it or lose it.” In order to fully utilize their respective exemptions, married couples often implemented a bypass plan: they divided assets between a marital trust and a credit shelter, or bypass, trust (this is often referred to as an A/B trust plan). Under the 2010 and 2012 Tax Acts, the estate of a deceased spouse can transfer to the surviving spouse any portion of the exemption it does not use (this portion is referred to as the deceased spousal unused exclusion amount, or DSUEA). The surviving spouse’s exemption, then, is increased by the DSUEA, which the surviving spouse can use for lifetime gifts or transfers at death.

Example: At the time of Henry’s death in 2011, he had made $1 million in taxable gifts and had an estate of $2 million. The DSUEA available to his surviving spouse, Linda, is $2 million ($5 million – ($1 million + $2 million)). This $2 million can be added to Linda’s own exemption for a total of $7,430,000 ($5,430,000 + $2 million), assuming Linda dies in 2015.

The portability of the exemption coupled with an increase in the exemption amount to $5,430,000 per taxpayer allows a married couple to pass on up to $10,860,000 gift and estate tax free in 2015. Though this seems to negate the usefulness of A/B trust planning, there are still many reasons to consider using A/B trusts.

•The assets of the surviving spouse, including those inherited from the deceased spouse, may appreciate in value at a rate greater than the rate at which the exemption amount increases. This may cause assets in the surviving spouse’s estate to exceed that spouse’s available exemption. On the other hand, appreciation of assets placed in a credit shelter trust will avoid estate tax at the death of the surviving spouse.

•The distribution of assets placed in the credit shelter trust can be controlled. Since the trust is irrevocable, your plan of distribution to particular beneficiaries cannot be altered by your surviving spouse. Leaving your entire estate directly to your surviving spouse would leave the ultimate distribution of those assets to his or her discretion.

•A credit shelter trust may also protect trust assets from the claims of any creditors of your surviving spouse and the trust beneficiaries. You can also include a spendthrift provision to limit your surviving spouse’s access to trust assets, thus preserving their value for the trust beneficiaries.

A/B trust plans with formula clauses

If you currently have an A/B trust plan, it may no longer carry out your intended wishes because of the increased exemption amount. Many of these plans use a formula clause that transfers to the credit shelter trust an amount equal to the most that can pass free from estate tax, with the remainder passing to the marital trust for the benefit of the spouse. For example, say a spouse died in 2003 with an estate worth $5,430,000 and an estate tax exemption of $1 million. The full exemption amount, or $1 million, would have been transferred to the credit shelter trust and $4,430,000 would have passed to the marital trust. Under the same facts in 2015, since the exemption has increased, the entire $5,430,000 estate will transfer to the credit shelter trust, to which the surviving spouse may have little or no access. Review your estate plan carefully with an estate planning professional to be sure your intentions will be carried out under the new laws.

Wealth transfer strategies through gifting

Because of the larger exemptions and lower tax rates, there may be unprecedented opportunities for gifting.

By making gifts up to the exemption amount, you can significantly reduce the value of your estate without incurring gift tax. In addition, any future appreciation on the gifted assets will escape taxation. Assets with the most potential to increase in value, such as real estate (e.g., a vacation home), expensive art, furniture, jewelry, and closely held business interests, offer the best tax savings opportunity.

Gifting may be done in several different forms. These include direct gifts to individuals, gifts made in trust (e.g., grantor retained annuity trusts and qualified personal residence trusts), and intra-family loans. Currently, you can also employ techniques that leverage the high exemptions to potentially provide an even greater tax benefit (for example, creating a family limited partnership may also provide valuation discounts for tax purposes).

For high-net-worth married couples, gifting to an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT) designed as a dynasty trust can reduce estate size while providing a substantial gift for multiple generations (depending on how long a trust can last under the laws of your particular state). The value of the gift may be increased (leveraged) by the purchase of second-to-die life insurance within the trust. Further, the larger exemptions enable you to increase, gift tax free, the premiums paid for life insurance policies that are owned by the ILIT or other family members. Premium payments on such policies are taxable gifts, so these premium payments are often limited to avoid incurring gift tax. This in turn restricts the amount of life insurance that can be purchased. But the increased exemptions provide the opportunity to make significantly greater gifts of premium payments, which can be used to buy a larger life insurance policy.

Before implementing a gifting plan, however, there are a few issues you should consider.

•Can you afford to make the gift in the first place (you may need those assets and the related cash flow in the future)?

•Do you anticipate that your estate will be subject to estate taxes at your death?

•Is minimizing estate taxes more important to you than retaining control over the asset?

•Do you have concerns about gifting large amounts to your heirs (i.e., is the recipient competent to manage the asset)?

•Does the transfer tax savings outweigh the potential capital gains tax the recipient may incur if the asset is later sold? The recipient of the gift gets a carryover basis (i.e., your tax basis) for income tax purposes. On the other hand, property left to an individual as a result of death will generally receive a step-up in cost basis to fair market value at date of death, resulting in potentially less income tax to pay when such an asset is ultimately sold.